Sexing

Being able to sex your tarantula before it matures is a useful skill that can help with planning future pairings. Here, we will discuss two different methods: molt and ventral sexing. Both are reliable, scientifically accurate methods of determining sex. Each method requires practice and attention to detail, and each has its own limitations. It is beneficial to learn both methods of sexing, as will be discussed below.

Molt sexing

This method involves checking the inside of the molted exoskeleton for the internal sexual organs. These are located directly between the upper pair of book lungs for both males and females.

By the time we notice a new molt, it has usually already dried into a twisted, folded up position. This doesn't mean the molt is unusable; it just needs to be rehydrated to soften the skin. Tarantulas are hydrophobic, and the skin will not readily absorb plain water. Adding a few drops of dish soap to your water solution will allow it to easily soak into the skin. Smaller molts (around 2" and under) may only need to soak for a few minutes. Larger molts may need longer (10-20 minutes or so) to soften. Use care when checking the molts to avoid tearing.

Once your molt has softened, gently untwist and unfold the skin, and spread it open as flat as possible. Make sure the internal side of the skin is facing up. The book lungs will appear raised and whiteish on the inside. Toothpicks can be used to open larger molts. For smaller molts, thin metal wires, such as those used for bread twist ties, work well after stripping off the paper/plastic coating. Lighting the molt from underneath will help to see the internal structures.

Larger molts, around 3" and up, can often be sexed with the naked eye. Smaller molts will require magnification via microscope or jeweler's loupe.

The pictures below show a 6" female Grammostola pulchra molt.

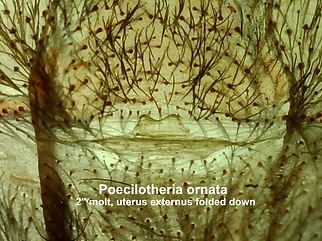

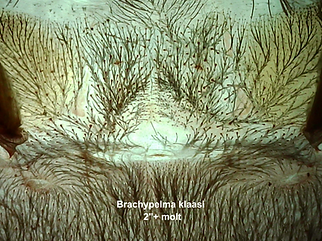

Slit sensilla are paired sensory organs found in both male and female molts. These will always be above the sex organs. Below the slit sensilla are the uterus externus and spermathecae. The uterus externus is a flat, translucent or opaque structure that rests against the spermathecae. It can be moved independently, and can be folded down to get a better view of the spermathecae.

Spermathecae shape varies widely across species, but are either paired or fused structures. These are also movable and can be folded downward. Spermathecae may be nearly transparent in smaller molts, but will darken as the spider grows and matures. Because the shapes are completely different across genera, it is helpful to research the specific shape for the species you are checking.

Encyocratella olivacea and Sickius longibulbi females are the only tarantula species currently known to science that do not have spermathecae. When sexing these two species, you'll be looking for the translucent uterus externus, which is still present. Below are spermathecae photos from various species. Notice the similarities between species within the same genus.

Below is a 5" male Acanthoscurria geniculata molt, photo provided by Greg Rice.

Accessory organs are paired but separate structures. They are small, and are not connected to each other at the base. They may be faint or difficult to see at all in smaller molts or with certain species. In other species, such as Acanthoscurria geniculata (above), they can be quite prominent, and can be folded down.

The gonopore is a small, rectangular or flattened oval shaped structure found centered directly below the accessory organs. This structure is not movable. Below are male molts from various species.

If you're not sure whether you're seeing male or female structures while the molt is wet, try letting it dry out and then check again. This can help make the structures more visible. Below is a pair of small Vitalius chromatus molts, still wet with soapy water.

Here are the same molts after drying.

Sometimes the molt has been damaged or completely destroyed by the spider. The best way to avoid this is to keep a close watch on spiders known to be in premolt, so the molt can be removed as soon as possible. Molts can be safely removed as soon as the spider has fully exited the old skin, before it has turned over and had the chance to damage it. Fluid is lost during molting, and spiders chew their molts to suck out the leftover fluid. Make sure water is available so it is able to rehydrate after this strenuous process.

Unfortunately, getting an intact molt isn't always possible. You may also wish to determine the sex of a spider you're considering purchasing, but the seller does not have a molt available. This leads us to the second method.

Ventral sexing

If you've kept tarantulas for more than a few weeks, you have likely heard the idea that "checking a molt is the only accurate way to sex a tarantula," or "ventral sexing is just a guess." These statements are factually incorrect, and really do the keeper a disservice. Neither method is "better" than the other, and both can be used to determine sex with 100% accuracy.

The science behind ventral sexing was described and being used as early as 1995 by arachnologist Rick West, with information found in the paper "The Spinnerets and Epiandrous Glands of Spiders" by B. J. Marples, J. Linneaus Society (Zool.), vol. 46, 1967. This website will try to do justice to the excellent but now missing British Tarantula Society article outlining this method.

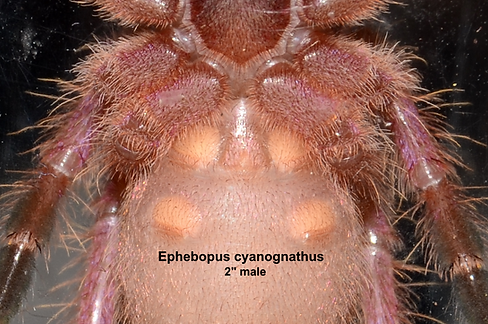

Ventral sexing is easier in person, but can be done with a sufficiently clear and well lit photo. This method involves observing the underside of a live tarantula, looking for the presence or absence of epiandrous fusillae. These specialized "hairs" are believed to aid in the construction of sperm webs, and are only present on male tarantulas. If you are looking for "female" when molt sexing, you are looking for "male" when ventral sexing.

Epiandrous fusillae are located between the upper pair of book lungs, directly above the epigastric furrow. As with spermathecae shape for females, the exact appearance of the fusillae varies between species. However, all species within a genus should look similar to each other. The fusilae may be darker, lighter, or nearly the same color as the rest of the spider's underside. They will be tightly grouped together in a well defined area, often appearing as a triangular arch.

For spiders around 2" and up, the fusillae patch can often be seen without magnification. A clear, unobstructed view of the ventral area is needed, and a flashlight is very helpful. Move the light over the spider, and look closely for a concentrated patch of hair that grows in a different color, length, direction, or density from the rest. In some species it will be very easy to see, and in others it is less obvious.

Below is a 5" immature male Pamphobeteus sp. platyomma. The fusillae patch is large, dark, and very easily spotted. There is no need to wait for a molt, this spider is 100% male.

Here is a 5" mature female Pamphobeteus ultramarinus. Note how the hairs are uniform in appearance, with nothing standing out. *This specimen has had the small growth on one of her lower book lungs for years. It doesn't seem to trouble her.

This 5" immature male Poecilotheria miranda appears differently. In this case, the fusillae patch is light instead of dark.

In comparison, here is an 8" female Poecilotheria rufilata. A smooth, uniform appearance.

Here are some photos of males and females of the same species and similar size. See if you can spot the difference.

The fusillae patch may be faint and harder to see on smaller specimens, but usually becomes bolder and more pronounced as the spider grows. Example photos of male Monocentropus balfouri at different sizes below.

Maturity

How can you tell when your tarantula is mature? For females, this happens when the spermathecae have sclerotized. This can be seen by a darkening of spermathecae color. Females are usually mature by around 3/4 full size, and continue to molt throughout their lives.

Males have an "ultimate" maturing molt, where all species develop bulbs at the end of their pedipalps called emboli. These are smooth, shiny, and reddish in color. They are tucked to the side and under the pedipalps.

The emboli can be harder to see in some fluffier species, but the shape of a mature male's pedipalps is unmistakable. The pedipalps of females and immature males look the same as the rest of their legs, ending with a "foot" and tiny claws. The last segment of a mature male's pedipalp is very short, blunt, and rounded. There is no "foot" and there are no claws. This is the best way to confirm maturity in male tarantulas, as every species will develop emboli and show this new pedipalp structure when mature. Below are some pedipalps in various angles.

Males of some species also develop tibial spurs or "hooks" when mature, which are used to secure the female's fangs during mating. It's important to remember that not all species have these hooks, and even in species that do, they may be smaller and not very easy to see through the "fluff" on the legs. Looking for tibial spurs should not be used as the primary method of checking for maturity.

If present, tibial spurs are located on the first pair of walking legs, on the underside of the tibia. Many species also show notable curving of the metatarsus when mature. This curve is only seen in mature male specimens.

Finally, the males of some species show striking changes in color when mature. This is called sexual dimorphism. This only occurs (with very few exceptions) after the males are mature. Below are a few examples. Mature male Aphonopelma moderatum photo and Pamphobeteus sp. machala photos provided by Greg Rice.

All photos on this page were taken by Emile Weber, unless otherwise credited.